by Scott Helmke

Welcome to the first in a series of posts about the practical theory for successfully using wireless microphones. Because this is such a big topic we’ve decided to break it into a series of smaller chunks, so stay tuned for future articles in this series.

How Does a Wireless Mic Work?

A wireless microphone works by transmitting a radio signal from the microphone (also called a transmitter) through the air to a nearby receiver. Each transmitter must have its associated receiver, which takes the radio signal and turns it back into audio so that it can be connected to an audio system. This works great and doesn’t require much thought, as long as you only have one microphone and receiver to work with. Each channel (one transmitter, one receiver) of wireless must have its own frequency to avoid interfering with other channels. The very cheapest of wireless systems don’t allow any tuning of different frequencies at all, while inexpensive systems have the ability to tune, but over a limited range. Professional shows that have a lot of wireless channels use the most expensive wireless systems, which are designed to have a wider tuning range and to work better in large systems. While we’ve used wireless microphones as an example, the same concepts apply broadly to all production wireless systems (IEM, wireless intercom, etc.).

What Else is the RF Spectrum Used for?

Beyond the need to simply have each wireless channel on its own frequency, the space that most wireless microphones work in is already filled with other transmitters, in particular television stations. The reason for this is mostly historical – before digital television (DTV) became available, analog TV stations had to be spaced apart from each other. In the USA every TV channel (both analog and digital) is assigned 6MHz of space in the frequency spectrum. VHF stations are assigned 54-88MHz and 174-216MHz, while UHF stations are assigned 470-608MHz. Early wireless microphones in the TV bands tended to use VHF frequencies, but eventually as technology improved the UHF band became the most popular space for microphones. The frequencies in the UHF band tend to work well for wireless microphones, allowing small antennas but still good distance – if you watch old concert films you might see some rather large antennas in the background for the VHF microphones. Joni Mitchell’s “Shadows and Light” film shows an antenna about 6’ tall right behind her onstage, to pick up the signal from her wireless guitar transmitter.

The open spaces between TV stations has generally been the most open space available over the whole frequency spectrum, and almost all of the rest of the spectrum has been claimed, assigned, and jealously guarded for other uses. There are a few safe spaces that have been designated as available for wireless microphone use, but almost all of the products currently available use the UHF band. But as analog TV has been replaced by digital TV, the need to provide empty space between stations has gone away. DTV stations can be packed tight together, leaving only enough room in between to fit possibly one wireless microphone channel. In the analog TV days a wireless microphone that had a tuning range of 30MHz could always find space between TV stations, since the TV stations had to be spaced out. The original UHF TV band went all the way up to 806MHz, most of it empty space.

What Does the RF Spectrum Look Like Today?

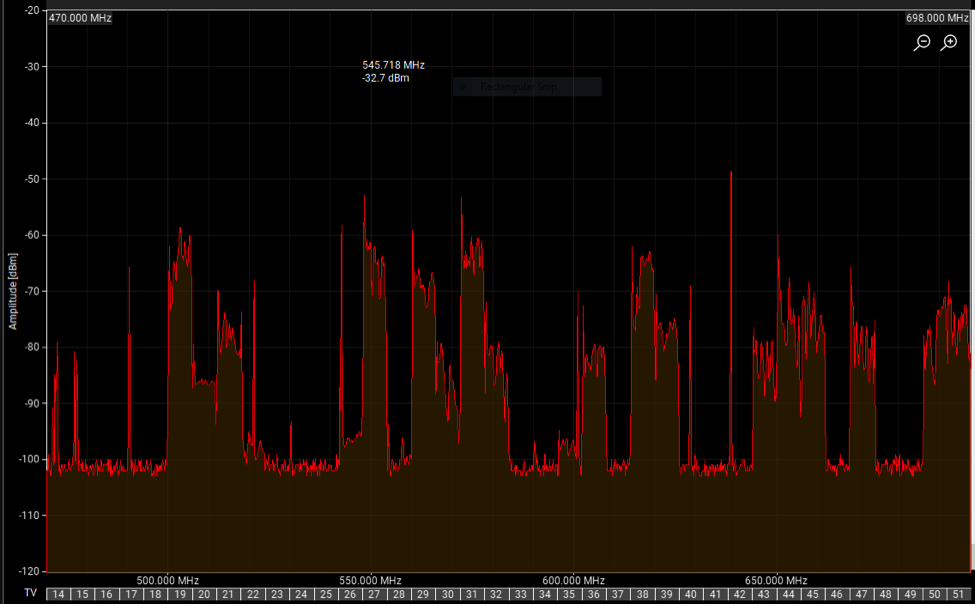

Here’s a scan taken in Chicagoland from 2017. All the blocks which look like city buildings are DTV stations. Any space in between those stations, aside from a small bit at the left of this scan, was legal for wireless microphones. You can see the TV channels at the bottom of the image:

Over the years the spectrum from 616-806MHz has been auctioned off by the government to companies for use in mobile phone and internet services. The TV stations that occupied that spectrum have been “repacked” into the remaining space, further crowding out wireless microphone use.

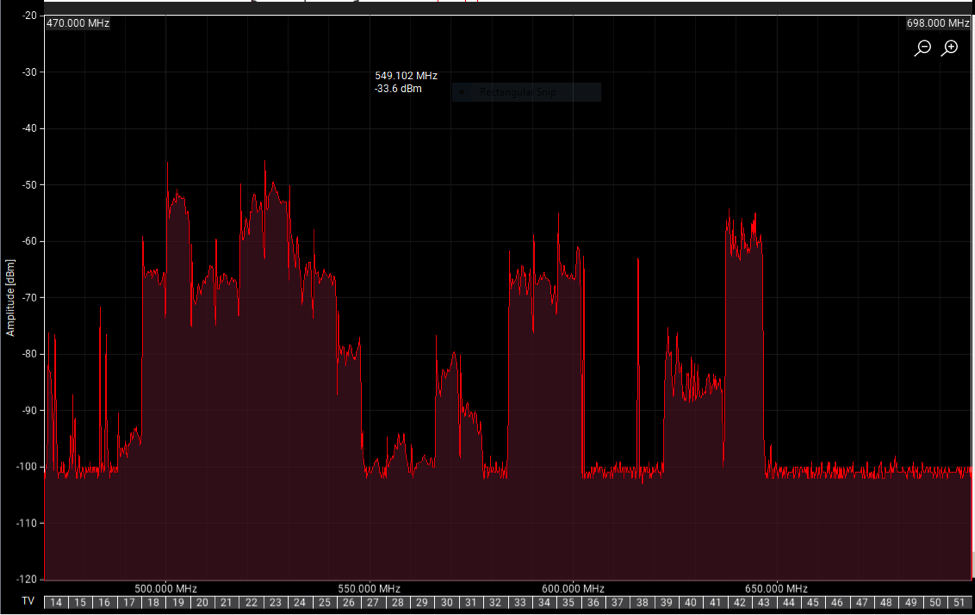

Here’s a scan from the same location from fall of 2020, after the most recent repack. The mostly empty space on the right side is now reserved for other services and not legal for wireless microphones. And some of the space at the left edge, channels 14 and 15, is not allowed for wireless microphones:

Back in 2017, before the latest auction and repack, there were roughly 17 open TV channels available in most of Chicago. Now, post-repack, there are only 9 open channels. Click here for more details on the 2017 FCC auction of the 600MHz band, and the 2020 repack.

What Does This Mean for You?

On to the practical. For finding good frequencies the first task is to figure out what TV stations are actually broadcasting in your area. Usually this can be done with manufacturer tools such as Shure’s Wireless Frequency Finder webpage, or their Wireless Workbench software. The ideal way to find all the local TV stations is with an onsite scan, which requires either a wireless mic receiver which can be networked to Wireless Workbench, or some radio scanning equipment. For just one or two wireless channels it’s enough to simply tune to a frequency not occupied by a TV station. And most modern wireless systems include some simple form of automatic frequency selection which can avoid active TV stations.

Finding good frequencies for a larger number of channels will be coming up in a future post. Stay tuned!

Stay tuned for the next article in the series. Next week’s topic: alternatives to UHF wireless. What other frequency bands are available for wireless users, and when should you consider them? Check back in for the answers.

Interested in purchasing a wireless system? Reach out to our Sales Team at 847-367-9588 or sales@tcfurlong.com for help selecting the right system for you.

We also carry hundreds of channels of wireless in our rental stock, and our experienced Project Managers can help design and implement a wireless system for your next show. Reach out to them today at 847-367-9588 or rentals@tcfurlong.com to get started.